‘You can’t take the coach out of him’

<< Go back

Ronnie Johns met Vicknair soon after moving from DeRidder to Sulphur in 1983, a year after beginning his career with State Farm. He moved for a better business opportunity, and it helped he had family in Southwest Louisiana. His only brother, Mike Johns, was coaching at LaGrange.

The connection between Vicknair and Mike Johns helped start a friendship between Vicknair and Ronnie Johns. The latter watched all three of Vicknair’s sons grow to manhood.

Common interests — cooking, spending time with family and friends — sealed the deal, and Ronnie Johns said he came to admire Vicknair more and more over the years.

“His whole thing was about young people,” Johns said. “He loved what he did, and he loved having an impact on young people.”

Growing up in a family with a coach, Johns saw behind the scenes, where fans rarely catch so much as a glimpse. The view enabled Johns to gain a deeper appreciation for Vicknair.

“I watch how dedicated and how many long hours these coaches put in, and Charles was like that, but the thing that I really admired about him the most was that when he came home from that school, he could leave it there,” Johns said. “He dedicated that time when he got home to his family.

“Debbie — that was his best friend. It really was. They did everything together. They enjoyed doing things together. They really enjoyed entertaining a lot, and we would do that together.”

|

If Vicknair wanted people to nurture and care for their corner of the world, he was a great teacher by example, Johns said. Whatever he did, he did with a passion.

Johns began having a regular pig roast, a cochon de lait, at his uncle’s house.

“From the time I lit that fire at 4 o’clock in the morning on, Charles was there,” he said.

The social element was an important link, but a love of food and a desire to try new foods and recipes had something to do with that too.

“He probably had as many cookbooks as Barnes & Noble,” Johns said. “He’d call me, ‘Man, you wouldn’t believe the new cookbook I got. You’ve got to come see this thing.’ I remember when they moved to their present location, he built that outdoor kitchen that he was just incredibly proud of. That was his sanctuary, being out there.

“He was just a wonderful cook. It wasn’t just rice and gravy, the typical man dishes that we usually like to cook: barbecue or sauce piquante or etouffee. He was an accomplished cook and was always trying something new.”

As busy as coaches are, Johns said, many don’t become involved in civic activities. When Vicknair was at Sam Houston, he became active in the Kiwanis Club in Moss Bluff, later becoming president and helping the group become of the most successful in the area.

Johns recalled members telling him Vicknair made it fun, bringing a different energy level to the club.

The Vicknair boys attended Our Lady Queen of Heaven Catholic School, and their parents helped organize a fundraiser. They asked Johns if he’d like to participate, and he agreed to work with them and others on putting together a Mexican fajita dinner for a group of two or three dozen people.

Debbie Vicknair said Debbie and Gerald Link, Rosanna and Jay Lafleur and Vickie and Gerald Smith joined the Vicknairs and Ronnie and Michelle Johns in coordinating the event.

They went the extra mile or miles, beginning with decorating a Catholic school bus in a Mexican motif.

“We actually had some live roosters on the bus,” Johns said. “Gerald Smith we called him ‘Killer’ we had Killer driving the bus, and we went and picked up everybody at their house and brought them out to the camp where we were actually cooking the dinner.”

“It was a fun time, and we raised a lot of money for Queen of Heaven,” Johns said, “and those are the kinds of things that he really, really enjoyed doing.”

People will tell you football was Vicknair’s life. Johns saw a different side of him, on weekends and away from the game.

People will tell you football was Vicknair’s life. Johns saw a different side of him, on weekends and away from the game.

“Those boys were his life,” he said of the three sons of Debbie and Charles Vicknair.

Charles, known as Little Vic, is the oldest. Johns became his mentor, teaching him the insurance business for about a year and a half. A year after his father died, Vic Vicknair was poised to become a State Farm agent in Katy, Texas.

Chad, the middle child and a registered nurse, moved into orthopedic equipment sales.

Cody, the youngest, went on to work in real estate.

“I nicknamed him ‘The Legend’ years ago,” said Johns, who used Cody Vicknair as his real estate agent when buying a house for his daughter before her November 2009 wedding.

In the wedding party: The Legend.

Hebert, who played for Vicknair at McNeese and later was his boss at Sulphur, said he saw father-son relationships in a different light because of his time with Vicknair.

“I always thought of Coach Vic as another father figure to me,” Hebert said.

If that’s true, Vicknair was the kind of father who knew when it was time for the son — or pupil — to be his own man.

“To have him work for you, and you’ve kind of got to tell him what to do a little bit and maybe correct him a couple of times, that was difficult,” Hebert said, “but he always made it easy.”

The more Vicknair worked for Hebert, the more the latter had a chance to see his personal life, which a child of the 1960s found revealing.

“You know that all our fathers weren’t loving and hugging and all that stuff, so just to watch him” was special, Hebert said. “He put notes in his kids’ ... when they went on trips he’d stick a note, telling them he loved them and he was proud of them, in their bag or something, that they would find.”

Hebert, who has a son, took a cue from Vicknair, updating the gesture for the times.

“We text now. I text him instead of sticking notes, but it’s still the same deal,” Hebert said. “It kind of teaches you how to still relate to your kids. I learned on both sides. I learned the football and family side from him. I loved him. Like I said, I thought of him as a father, and it was just good being around him, working with him.”

The more Johns and others talked about all of the areas of Charles Vicknair’s life the late coach tended to with attentive devotion, the more Vicknair’s energy level took on an almost legendary quality.

He drove often to Alexandria to see his mother when she lived there, and after moving her to Lake Charles when she was in her 80s, he had coffee with her every morning unless he was out of town.

“He was just very, very dedicated to her,” Johns said.

Family meant something to him, and he was proud he and Debbie could see three sons graduate from LSU.

“To be able to send three kids to LSU on a coach’s salary is pretty tough,” Johns said. “It’s not easy, and they sacrificed a lot to be able to do that, but that was what was important to him.”

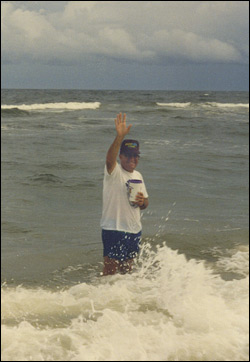

Along the way, there were laughs. During a beach vacation enjoyed by the Johns and Vicknair families, Vicknair waded out into the water for a bit, then came back to join the others back on the beach. He reached inside his swimming trunks and pulled out his cell phone, which had been with him the whole time.

Along the way, there were laughs. During a beach vacation enjoyed by the Johns and Vicknair families, Vicknair waded out into the water for a bit, then came back to join the others back on the beach. He reached inside his swimming trunks and pulled out his cell phone, which had been with him the whole time.

“You know what salt water does to a cell phone?” Johns asked, not expecting an answer.

The story is even better when you learn, as Johns did, that three weeks earlier the same thing happened during a Vicknair family vacation.

“Debbie was all over his case about him ruining two cell phones in about a three-week period,” Johns said. “Typical him, he just laughed about it. Surely he wasn’t upset about it.”

Football, coaching, teaching, cooking, socializing, civic work ... was there anything else Vicknair found time for in a 24-hour day? Yes, said Johns, a former state representative.

“In the 12 years I served in the Louisiana Legislature, he discussed politics with me at a level that not a whole lot of people would,” Johns said. “He kept up with it. He was interested in it. He understood it. It surprised me at first that he would have an interest in that, and it wasn’t just about football with him, or with other sports. It was about being very well-rounded in a whole lot of aspects, and he had a great interest in politics. We spent a lot of time, a lot of nights, particularly in that 12-year period, talking about political issues, and he was very well-read and very well-educated in that arena.”

There was the occasional swing of the golf club, but Vicknair found it required too much time to work on the finer points of the sport, and Johns said it never became a regular thing.

“Ronnie, I don’t have time for that,” he recalled Vicknair telling him.

Johns said he misses the time they spent together, especially cooking on weekends.

“There’s a void there,” he said.

The 12 months between Vicknair’s death and the first few weeks of the following football season drove home that gap.

“The football seasons are when a lot of people will think about him and miss him,” Johns said, “but in my case, I miss him almost every weekend, because that’s when we spent our time together.

“I miss him. I think about him a lot.”

Johns said one of his favorite stories about Vicknair was a reminder of his passion for teaching the game of football, even to boys who didn’t play for him. Vicknair’s place in the world, his bubble, was far-reaching and generous.

About a year before Vicknair died, Johns said, their families were vacationing at Orange Beach, Ala. While they sat on the beach one morning, they noticed some kids throwing a football while they ran around on the sand. Vicknair began talking with the father of one of them and found out the son was soon to be a high school senior and was receiving attention from college coaches. That was all it took.

About a year before Vicknair died, Johns said, their families were vacationing at Orange Beach, Ala. While they sat on the beach one morning, they noticed some kids throwing a football while they ran around on the sand. Vicknair began talking with the father of one of them and found out the son was soon to be a high school senior and was receiving attention from college coaches. That was all it took.

“Instead of sitting there and enjoying himself and relaxing,” Johns said, “he spent most of that morning out there coaching that kid on how to throw a football and giving him some pointers on this and that. He was coaching on the beach in Orange Beach, Ala.”

That’s what he enjoyed doing, whether it was at a high school, at McNeese or a summer camp at another college.

“You can’t take the coach out of him,” Ronnie Johns told his wife that night.

“Here was a kid he never met before, that he would never see again, and he spent half of his vacation day coaching him on the beach.”

Johns said Vicknair often asked him how his oldest son, Vic, was doing as he learned the ways of the insurance industry through the coaching of Johns.

“When I had the opportunity to do something for his son,” Johns said, “I never hesitated to jump on that opportunity, and now, God bless his soul, he’s not around here to see it, but his son is going to have an incredible opportunity to have a great business career, and that’s what he wanted for his son.”

Johns didn’t miss the connection between what he’d seen of Vicknair as mentor and what Johns had become for Vicknair’s oldest boy.

“Charles kind of played a part in showing me that you needed to do that for these young people,” he said.

Discussion Area - Leave a Comment