His three sons

<< Go back

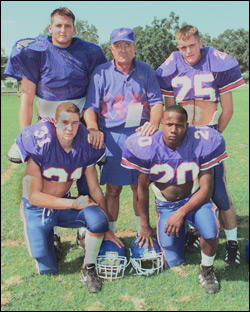

Coach Vic coached his three sons at St. Louis. Charles “Vic” Vicknair, Class of 1997, was a linebacker. Chad Vicknair, Class of 1999, was a free safety. Cody Vicknair, Class of 2001, was a linebacker.

“I played with both of them,” Chad said. “Vic didn’t play with Cody, but I played with Vic and I played with Cody.”

Vic was a freshman at St. Louis in Vicknair’s last year at Sam Houston. When Vic was a sophomore, his dad was an assistant with the Saints. The next year, he became head coach.

“I was a freshman at that time,” Chad said. “My freshman year I didn’t play, but my sophomore year, I started. I was a free safety. Vic was a linebacker. We played on the same side of the ball, which was a unique experience — one, because not many people get to experience that, and two, we knew the head coach.”

That’s no small thing. It’s common for high school players to have reservations about the new coach, but in this case, familiarity bred a comfort zone among the Saints.

“With Vic and his friends and me and my friends, who all grew up around us and knew our dad, they could automatically feel comfortable and trust him, and anything he said, we could do, and we knew he was doing it for the right reasons, whether it be on or off the field,” Chad said.

Coach Vic wanted them to do it for themselves without him directly coaching them.

“There was certainly no favoritism,” Vic said. “He didn’t hesitate to jump one of our asses if we did something wrong, and that was fine. We expected it.”

Their father coached on the other side of the ball, on offense, so those moments were rare. There were other coaches more directly in line to handle that.

“He would not hold back any coach from doing whatever they had to do to punish us, coach us, teach us, to make us become a better player,” Cody said. “He made sure the coaches knew that, and they did, and so they drilled us harder than anybody else.”

The boys said Vicknair was fair, treating every player the same. He gave them a lot of respect, and they returned the favor. The sons grew up knowing he did things professionally, at 100 percent, they said, so they expected nothing different when they played for him.

Still, Cody said playing for his dad was one of the hardest things he’s ever done.

“Where do you draw the line between a coach and a dad?” he said. “It was one of the most special things, but also one of the most difficult. You want to please the coach, but you also want to make your dad happy. Where you find that balance was kind of tricky for me. You don’t know whether sometimes on the field to call him Coach or Dad, so you just give everything 120 percent because you want to make him happy — and because it all reflected on you.

“The one thing I can tell you, when we talk about a coach and their son on the field, we were probably his biggest critics, because he did not show any favoritism to us by any means whatsoever.”

Their mom, Debbie, remembered Chad getting hurt in a game. Coach — Dad — went to check on him.

“If Chad was down, he was hurt,” Debbie said. “He was that kind of kid.”

Debbie’s recollection is the father and coach of her sons told her middle child something that later make all of them laugh.

“OK, your momma’s watching; get up and get off the field.”

Almost a year after losing her husband, Debbie smiled when she remembered that story.

“It was hilarious,” she said.

Months after Debbie told the story, Chad remembered and gave his version. It was his only injury, he said, and it came when South Beauregard ran the guard-around trick play. Chad saw it coming, and when he tried to tackle the 300-pound lineman with the ball, a wide receiver blindsided him.

He couldn’t breathe, and trainers ran out to him on the field. His dad was there too.

“He looks at me and he says, ‘Get up. Your momma’s over there worried about you on the sideline, so come on.’ I got up and walked off, and in retrospect looking at it, it’s pretty funny. I guess it says a lot, that he was always worried about Mom on the sidelines even though he had to coach a game and try to win. Now that I look back on it, it was pretty funny.”

Cody recalled the few injuries he and Vic suffered during games.

“Dad wasn’t the first one out there,” he said. “The other coaches were. He knew we were all right. He didn’t come up to us after games, not like a father would come up to a son and ask. He took care of the team. He knew he’d see us that night. He knew we were all right.

“But when he would come home, dad was dad. Dad wasn’t Coach Vic at the house. He would take care of family things and keep the relationship between the son and the father, but at the same time still talk football.”

Of course. All three boys were fall arrivals. The doctor who handled one of Debbie’s pregnancies called one day to ask her if she was ready to give birth, and she checked with her husband before giving an answer.

“That might work out well,” she remembered him saying. “We don’t have practice this afternoon.”

Years later, the boys tagged along at times to be with their dad at the office.

“They’re all grown now, but I remember when they were running around in diapers,” Siebarth said. “We’d be watching film in the film room, and here comes little Vic.”

“They’re all grown now, but I remember when they were running around in diapers,” Siebarth said. “We’d be watching film in the film room, and here comes little Vic.”

As they grew up, they learned that if they were going to see much of the coach in Coach Vic, they would have to go to the office. At home, he really was Dad.

“It’s funny, because he had never brought his work home,” Vic said. “If we were home and were having dinner, we’d ask how practice was. ‘Oh, it was great.’ He would always tell you it was good. It was not like he would have a bad day and come home and take it out on us. It was always good.

“He was always Dad.”

“Unless we brought it up,” Chad said. “There were times when I would ask him questions — do I need to do this, do I need to do that — but only if we brought it up.”

Vic said there was seemingly nothing their father wouldn’t plan for, just in case.

“He even had Chad and I during the summers throwing the ball as a backup quarterback,” Vic said. “We were working those drills, and you’d do that at lunch, and then we were with the receivers, and after that it was weight training.”

“And we never saw a snap at quarterback,” Chad said, laughing, “but we’d have to go throw and do drills. We didn’t second-guess him. We said, ‘OK, let’s go,’ and we did it.”

The boys remembered their father taking trips to Alexandria, where he grew up and played for Bolton High School, and where his mother stayed until the last few years of his life. Vicknair would visit Butch Stoker, longtime coach at Alexandria Senior High, and draw up plays with him. Coach Vic would drag the boys to a coach’s office and talk about football for up to four hours, or what seemed like it to young boys. They couldn’t imagine someone talking about the game for that long at one stretch, but they learned that was their dad’s passion for the sport.

Mike Veron, a Lake Charles attorney and sports enthusiast, would often tease Vicknair.

“You’ve been doing this how long? You’re still going to school for it? You’re still trying to learn?”

The sons said Vicknair’s ever-changing schemes and new approaches were based upon his knowledge of the talent he had coming back in a given season and what he thought his players were capable of doing.

Despite his penchant for change, Vicknair remained an old-school teacher in the classroom during civics class or other courses he taught, Vic said.

“There were no PowerPoint presentations or projects,” Vic said. “He made you outline every chapter of the book, bring your notes to class, take notes — don’t forget your book — and there were no group projects. He lectured from the start of class until the end.”

Those who worked for him were students in a different way, as the boys discovered.

“He would take his coaches away before two-a-days for a weekend,” Chad said, “to a camp or somewhere. It could be hours away. They would have to sit there all weekend, and he would go over what their job was, each coach, what they were going to be in charge of for the season, and they would break each position down and talk about it, all the way down to form tackling.

“I had a coach tell me, ‘We went over form tackling before we started two-a-days.’ (laughing) It seemed like it was a mini-camp for the coaches, and this is how the season’s going to go, and that’s how organized he was. This would go this way, and practice would go this way, and special teams, offense, defense.”

One summer Vicknair was writing a defensive playbook. After he died, the boys found it and looked at it, and they remembered when he was working on it at home. He would break down each player on the defense and explain his role, how it fit in with the team, how the player’s mental and physical makeup worked within the team concept and many other details.

“The organization of it was just amazing,” Chad said. “I’ve never seen it before. He’d go out to our cookhouse for hours a day and start that playbook each day until it was completed, working on the white board. It was fun to see the progression of it, because you never get to see behind-the-scenes type stuff like that.”

Organization was of paramount importance, whether it applied to football or family vacations, the boys said, laughing at the memories. Clark Griswold of the National Lampoon “Vacation” movies had nothing on Vicknair when it came to planning trips in intricate detail.

“We’re waking up at this time, we’re getting in a van and heading it, we’re going to be at this city at this time, we’re going to eat here,” Chad said, recalling their father’s instructions down to the tone of voice.

“One of his things is he never liked to be late,” Vic said, interrupting Chad’s trip down memory lane. “It would aggravate him waiting to go to church on Sunday and Mom was still in the back trying to get ready. (Our Lady) Queen of Heaven was two minutes down the road, but it was 10 minutes to 9, and we weren’t in the van getting over there. I kind of got that from him. He was a pretty punctual person.”

They’d go snow skiing, and Vicknair drove. They’d pile in a van with a VCR and movies on videotape, and he’d drive all night. The boys couldn’t believe his stamina.

“He was the first one to get to the office and the last one to leave,” Chad said. “Always.”

“He always went to bed early,” Vic said. “Eight-thirty, nine o’clock, he was in bed. He’d wake up at 5, 5:30 in the morning and he was up and going.”

At one point in Vicknair’s career, players’ moms would ask more and more frequently about what was going on with the team, game plans, and why things happened the way they did.

He was asked often enough, he said, “OK, let’s watch film.”

“He started inviting the parents to come out on Monday nights and go over film, the previous game’s film,” Chad said. “I think a few parents came, but it mainly started being a lot of the moms. He started breaking down films for the moms and explaining the positions and why things are happening, this is a run, a pass, and this is what the linebackers do, and I want to say he would spend almost two or three hours with the moms, going over film with them.

“They were enjoying the hell out of it. He would pick with them and have fun with them, but I’ve never heard of any coach doing that with parents, taking the time to say ‘This is what’s going on, this is what you’re looking at, and this is what your son is doing,’ and I remember stories coming out about those moms being tickled to death about knowing what’s going on out on the field at the time.”

As the first anniversary of his father’s death approached, Cody sat in his mother’s living room and talked about seeing his father as a coach before and during the years he played for him at St. Louis.

“One thing I knew about him that amazes me still today is that he was always open to learning,” Cody said. “He never put himself above anyone else. He always acted like he was a first-time guy — first year doing this, first time doing this — and his teaching ability just surpassed anything I ever could have imagined of an educator, a coach and a dad.”

One aspect that stood out for the son was the father’s way of connecting with different people.

“He found a niche to not just be able to work with his coaching colleagues, but players, players of different backgrounds, players who were rich, players who didn’t have money, players who had to walk to practice every day. He was able to connect with everybody no matter where they came from.”

He would talk the same way to a coach from LSU as he would the water boy or managers of his team, the son remembered. Everyone was treated the same, and each day was always about teaching, about coaching.

“It never got old. Every day he walked up with the same amount of energy like it was his first day on the job. I just never could understand.”

The boys had trouble remembering a day he missed school or practice, and that was typical of the kind of consistency of work ethic he instilled in his players and assistant coaches.

Saint Louis, 1997

|

“He walked the walk, and he talked the talk, and that was very evident as a son, as a former player, and I think that’s what mom saw throughout her 31 years of marriage with him,” Cody said.

He remembered his father’s pregame and postgame speeches, becoming animated as he told a story about one his brother experienced when St. Louis went into a game as an underdog. Vicknair had a way of pacing, of walking back and forth, and that’s basically all he did before getting to the point.

“Let’s go kick their ass.”

The way the players from the Class of 1997 remember it, the entire room went crazy, and the Saints won and went on to compete in the playoffs.

Discussion Area - Leave a Comment