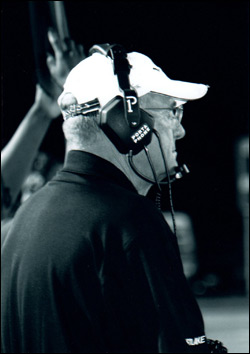

No one remembers exactly when it started, but somewhere around the time his fourth decade of coaching gave way to the start of his fifth, Vicknair began hearing the same question again and again.

“When are you going to retire?”

Max Caldarera asked. Jimmy Shaver asked.

Max Caldarera asked. Jimmy Shaver asked.

“Why are you still coaching?”

Debbie made a good point in September 2009.

“Well, look at them,” she said, a year after her husband’s death. “Look at Max and Jimmy. They’ve been doing it for a long time.”

She said her husband told her 2008 would be it, but she wasn’t so sure he meant it.

After he left LaGrange following the 2005 season, asked to resign after a winless season wrecked by hurricane season, he was looking for another place to work. Caldarera found himself on the verge of hiring as an assistant the very man who hired him to be a Westlake assistant three decades earlier.

Caldarera didn’t know how Vicknair would accept working for him, but they talked and talked.

“I need a job,” Vicknair told him. “I want to coach. I’m not through coaching yet.”

If he got the job, he would be returning to the town where his coaching career began in 1964.

Former Westlake principal Gary Anderson played football at the school in 1967-68 as a senior. Vicknair was there as an assistant coach, working with the offensive line.

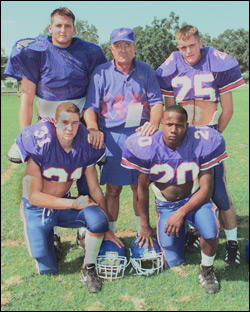

“He wasn’t your typical coach as far as not interacting with the rest of the faculty,” Anderson said. “Nobody outworked him. Sometimes that ran some kids off, but those that played for him respected him as a coach.”

Anderson, who spent eight years as assistant principal and nine as principal at Westlake before taking an administrative position with the Calcasieu Parish School Board in 1997, remembered the concerns about Vicknair’s ability to work for another head coach after many years of running the show.

“That was a question I had in my mind: How good an assistant coach could Charles be?” Anderson said. “He’d been a head coach for years, but he and Max had that kind of relationship where it worked out well for them. I don’t think there were many problems at all.”

Vicknair had been an assistant at Sulphur to start the decade, but the subject came up during his interview at Westlake. He said he didn’t think he’d have a problem. Anderson knew Vicknair had not been real successful at the end of his stay at LaGrange, but he understood some of the reasons.

“I think those kids at LaGrange weren’t used to the type of work ethic that Vic demanded out of his players,” Anderson said. “I just don’t think he got some of the players that could have been playing for him because of that, that it just wasn’t instilled in them at that point.”

Vicknair was long past the point of having an ego that required him to be a head coach. In fact, after spending the 1994 season as an assistant at St. Louis, he became head coach of the Saints only because Jim Hughes vacated the position, and the school asked Vicknair to take over the program.

“I’m still mad at Jim about that,” Vicknair told the American Press, tongue in cheek, in an interview just before the start of the 1995 season. “I spent my time as a head coach. I really didn’t want it. Just give me some kids to coach, and I’d feel comfortable. But this happened so late, I had to take it.”

Just give me some kids to coach, and I’d be comfortable. That, in a nutshell, was Charles Vicknair, whether he was on a beach during a summer vacation and saw a boy throwing a football, or one of his friends and colleagues needed his help.

When he and Caldarera talked about him joining the Westlake staff in 2006, Caldarera said: “As long as Westlake wins, I don’t care who gets the credit. Make us better.”

Some of the dynamics of their new relationship had yet to be worked out completely.

“Every now and then,” Caldarera said, “we’d butt heads a little bit. ‘Hold it. You forgot: I’m the head coach.’ And that happens, sure. It’s going to happen. It’s just like a damn marriage. There are going to be squabbles in coaching, on the staff, but it always worked out good.

“Whenever we got through with the meeting or the fussing and everything else, well, we went in the same direction.”

Caldarera began the 2009 season saying Vicknair’s impact on Westlake’s special teams was still evident, even without him.

— — —

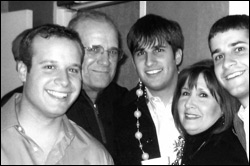

Sitting in the home his parents shared, Cody Vicknair spoke solemnly, but with a smile, as he talked about the final full day of his dad’s life in September 2008.

“That last day was something,” he said. “His mother was almost 90 years old. He was so proud of that. ‘Mother, you’re about to turn 90,’ he’d say. When we had lunch with her, she said, ‘He was so tickled I was going to turn 90.’ She was talking about dad at that last visit with her, on Sept. 19, before the Sam Houston game. They had a great visit.

“That last morning he did share with her, ‘Mother, I’m glad you’re happy here. It really makes me happy.’ Well, he questioned her. ‘Are you really happy?’ She said, ‘Yes, I am.’ And he said, ‘Good, because that makes me happy, and I love you, and I just want to make you happy and I want to tell you that.’ ”

Saying they’re not a real “lovey dovey” family, Cody said his grandmother told his father to stop talking that way, asking him why he was so directly expressing his love for her.

“He said, ‘Mom, I just love you. I just want to tell you that, and I really think this will be my last year.’ She said, ‘Charles, you say that every year.’ He said, ‘No, mom, I’m telling you. I think this is it. I want to be able to spend more time with the family and you,’ and he gave her a hug and a kiss, and he told her he loved her again, and that was the last time she saw him.”

Enez Aldret celebrated her 90th birthday in July 2009 in the same nursing home where her son, Charles, visited her at 6 every morning for coffee and conversation. She lost weight after he died, unable to force herself to eat. By December 2009, more than a year after his death, she’d regained some of the weight and said she felt good.

“Every time he’d have to help me in the truck, he’d tease me and say, ‘Momma, you’ve got to lose some weight.’ Now, if he knew I lost weight, he’d be thrilled over it.”

It’s impossible to imagine him being happy about the reason for her weight loss.

“I had some bad mornings,” she said. “Bad. I wouldn’t tell Debbie and the boys that, but Debbie knew what I was going through because I knew what she was going through.

“I came down here, and two or three of the ladies that knew him would always come over and talk with me, and that’s all I was able to do, sit and talk with them. Oh, I missed him. Very much. I still miss him a lot. The first year without him was the hardest.”

Mornings would never be the same without his visits. During her four years at a different Lake Charles nursing home, residents and staff would come to the dining area to see him when he visited his mother each morning. Vicknair would pick at them, as he did with everyone, and they loved it.

“He had to ring the bell, and the aides would know it was him, and they’d say, ‘Look who’s there: Pest is here.’ They called him Pest,” Vicknair’s mother said.

Other residents, including many who didn’t have a frequent visitor, would come downstairs to see Vicknair when he had morning coffee with his mother.

“They loved hearing him talk about his football teams,” she said. “They’d come down from their rooms and have coffee, and he’d cut up with them. He was the type of person where he had something smart to say — you know, cut up with them.”

She’d only been at her new nursing home a couple of weeks when her son died, and on the day before he died, when he came for a Friday morning cup of coffee with his mother, he wanted to make sure she was happy at her new residence.

“I said, ‘Don’t worry about me anymore. I want you to quit worrying about me.’ He said, ‘Well, you know I’m going to worry about you a little bit.’ I wasn’t a sick person. I’m not a sick person. I’m a diabetic. That’s about all.

“The last time I went to the doctor he told me I don’t have a speck of arthritis. I asked him how he knew that, and he said the tests showed it. All the ladies here can’t get over it. All of them do have it.”

Vicknair was rarely sick — “Just baby diseases,” his mother recalled — and when he died, no one who knew him could remember him being in the hospital for anything other than visiting someone else.

He tore his ACL at McNeese — in the school’s media guide, he’s listed as a letterman in 1961, and never again — and he didn’t undergo surgery. He wore a cast, then lived the rest of his life with the aftermath. By his 50s and 60s, the cartilage was gone, and it was just bone on bone, family members recalled.

“He died with that bad knee,” his mother said.

So was he really considering retirement?

“That morning the day before he died,” she said, “he told me, ‘Momma, you know what? I’m not going to have a team next year.’ … I said, ‘Charles, don’t talk like that. The season’s not over with yet.’ He said, ‘No, I think I’m going to retire.’

“I said, ‘Now, I’ve heard that before. I’ve heard that so many times, that you told me that you were going to retire, but you haven’t done it yet.’ ”

She said he pressed on about it.

“He said, ‘Mother, I’m not sick, but I got my kids through school. That’s what I wanted.’ He did. He did just exactly what he wanted to do. He said, ‘Mother, you know I love you,’ and I said, ‘Yes, I know you do.’ He was a great son to me, and I couldn’t ask for any better son than him.

“He did what he wanted to do. He wanted to coach, and he did that for 45 years.”

Those sons he and Debbie put through school took different professional paths than he did.

“He said, ‘Well, I thought maybe one of them would be a coach, Momma, but that’s OK. I’m still a coach, and I will be until I die.’ That’s what he told me,” his mother said.

Sitting in the dining room where she had her last cup of coffee with her son, she mentioned how often visitors will talk about him.

“My God, do I miss that man,” she recalled one man saying. “I said, ‘Well, I do too.’ And I do. I still miss him. I miss him every day. I think about all the things he did for me. He did so many good things for me.”

— — —

As he sat in his parents’ home amid souvenirs of his father’s coaching career, the youngest of Vicknair’s three boys paused to choose his words carefully.

“The one thing I’ll tell you about Charles Vicknair is that he lived every day like he knew it was going to be his last,” Cody said, “and that’s how we live today.”

The son became teary-eyed as he recalled Westlake winning that last game, at Sam Houston, the night before his father died. At this point, the story came from places within Cody Vicknair where linear chronology wasn’t necessary. He was letting stream-of-consciousness touchstones guide him.

He looked at his mother, and he recalled having a conversation with the sons of other coaches.

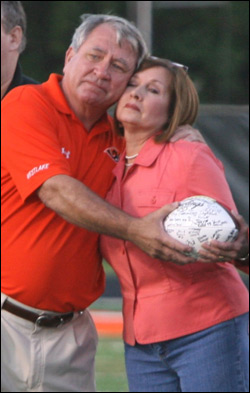

“Dad helped her be a coach’s wife,” he said. “The sons of coaches notice most of the wives become strong, disciplined women. That’s what we notice we have, a strong, disciplined mother. I look back now, at how things happen, and you start to ... it starts to make sense.”

Speech was becoming harder as his throat filled with emotion.

“It starts to make sense,” he said, “that the reason why things happen the way they are, the reason ... if I can make any sense of ... the reason why he was so tough and so disciplined, it’s because he prepared us for this time in life. The coaching and the fatherhood that he gave us was to prepare us to get ourselves together to go on without him.

“He prepared my mother too.”

There is a term, accepted without the blink of an eye in most circumstances, describing what football seasons are like for many women whose husbands are coaches, players and even fans. There is no harm intended, nor any harm felt, when the casual term “football widow” is employed, sometimes jokingly by the wives themselves. After the death of a coach, there is a bite and a burn in that expression.

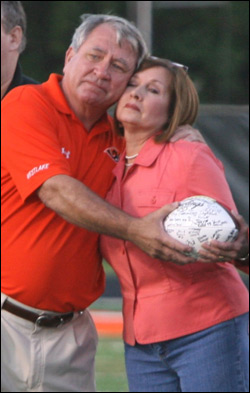

Debbie Vicknair, who will never hear that term in the same way again, didn’t describe herself like that, saying she always felt connected with her husband even during the busiest times, largely because the two of them worked at seeing each other as much as possible. Early wakeup. Dinner together. Getaways when they could.

“Debbie was always an incredible mother, an incredible supporter of Coach Vic,” family friend Ronnie Johns said. “You knew where you’d find her on Friday night in the fall — in the stands. She wasn’t a stay-at-home coach’s wife. She was there to support him through the good times and the hard times.”

Now that Vicknair is gone, the void is unmistakable, but the family said they have the benefit of a large support group created by Vicknair being who he was — a person who touched many lives.

When Debbie looks back, just like her youngest son did, she views the past in a different light too.

Coaches’ wives have to do a lot because the coach is gone so much, and that was true for her. She finds a deeper meaning in it now that her husband is gone and isn’t coming home.

“It was all in preparation,” she said.

In the larger view, it doesn’t seem at all unlike Vicknair to be preparing others for the future.

Bruchhaus never played as a lineman, but he started out coaching offensive line. Then Vicknair switched him to defensive line. Then he wanted him to coach something else.

“He wanted to teach you the whole game,” Bruchhaus said. “I didn’t understand why, but I understand why now.”

When he said that, a year after Vicknair’s death, he was no longer in coaching, but he knew his career would not have reached the heights it did without his mentor forcing him to prepare for as much as possible early in his career.

“I’m glad he took an interest in me,” Bruchhaus said. “I’m glad that I was smart enough to try to do what he wanted me to do.”

— — —

And so, the start of the 2008 football season, delayed by another active hurricane season, had the potential to mark the final season for Vicknair, at least if his comments to family members were to be believed.

“It could have been his last year,” Cody said. “It turned out to be what I call his final retirement.”

Westlake couldn’t play its first game in 2008 because of Gustav, its second because of Ike. The game at Sam Houston was the season opener.

In his office overlooking the football field at Westlake a year later, Caldarera briefly shifted gears, away from Vicknair’s final game to the discussion they had when he agreed to work for Caldarera as a Rams assistant coach. Every coach on the staff has an extra duty, and they needed to assign one to Vicknair.

“I’ll take the equipment room,” Caldarera recalled Vicknair telling him.

“He ran a tight ship in there,” Caldarera said.

Taking care of the grass on the field became an increasingly important role for Caldarera over the years, after Vicknair joined the staff, “he really worked me over about that practice field,” Caldarera said.

“The spring before that last season, we put five tandem loads of sand, spiking it, leveling it, just to make him happy,” he said. “We had to get it right.”

Westlake installed a synthetic playing surface on the stadium field after the 2007 season. Vicknair never coached a game on it. The Rams practiced and scrimmaged on it, but the hurricanes took away the early home games in 2008, so the only game he coached was at Sam Houston.

Caldarera said Vicknair spent time in the summer of 2008 in one of the offices overlooking the field, watching workers install the synthetic turf. He was fascinated by it.

When the season opener finally rolled around on Sept. 19, 2008, Matt Viator went to the game in Moss Bluff, where he began as an assistant coach under Vicknair in the 1980s. Viator said he knew Vicknair was having fun at Westlake, and he wanted to visit with him before the start of another season.

“What I do remember is at 6 o’clock, when they put the music on in the press box, he got mad: ‘I hate that music.’ It was nothing out of the ordinary.”

Westlake won, and when it was over, Vicknair was talking about the uniforms. Caldarera said the Rams had a new set of jerseys, and Vicknair was concerned about how they were going to clean them after a game on a wet field.

“We’re going to wash them,” Caldarera said. “Don’t worry about it.”

Not good enough.

“But listen,” Vicknair said, “we need to soak them, and … ”

“We need to do this, we need to do that,” Caldarera remembered hearing, the specifics escaping him one year later.

“He worried about different things, now,” Caldarera said. “He worried about whatever he was in charge of.”

Debbie made Vicknair a sandwich when he got home, and they went to bed. Before sunrise, she could tell something was wrong. She had trouble waking him.

Rushed to the hospital, Vicknair was in pain. Word spread there was a serious problem, and coaches and friends headed to the hospital.

He died soon after. The cause of death: an aortic aneurysm.

The possibility of a long convalescence or a slow, torturous death was something the family couldn’t imagine, and in that way they counted their blessings.

“He wouldn’t have wanted to go any other way,” Cody said.

“No,” his mother said, agreeing with him. They both seemed confident he’d have wanted to be coaching up to the last day of his life, that he would have been restless in retirement.

“He had never been in the hospital,” Cody said. “It was such a shock. He wouldn’t have wanted to be crippled or in any other state of mind.”

His friends and colleagues were stunned when Debbie called them early that Saturday morning, and they rushed to the hospital. He died before they could get in to see him.

Shaver said the hospital lobby was like a coaching clinic, a gathering of men who coached with Vicknair and for Vicknair.

“Debbie gave us all an opportunity to go in individually in the room and visit with him before they brought him away,” Shaver said, “so that was a special time. I wish he had been alive to hear the things we had to say, but he never really ... Vic was not a guy that you talked about personal things like that too much with. It was all rough. He was a rough talker. There wasn’t any ‘I love you, man,’ you know what I mean?”

A year later, Caldarera tried to put it in perspective.

“It was just a shock and a blow,” Caldarera said, “and a blow that it took a long time for this program to get over, and we’re still trying to get over it a little bit right now.”

The Vicknair family asked Matt Viator do eulogize the coach, so he went to their house that Sunday morning. They sat outside, and Viator opened a manila folder he brought with him. When he did, the Vicknair boys looked at each other.

“They looked at each other,” Debbie Vicknair said, “like ‘Oh my God.’ Charles had reams of card stock. That’s all he ever wrote on. And when Matt opened his manila folder, that’s what he was writing on.

“This is the Coach Vic thing.”

The card stock. The manila folder. The pen on the shirt, just in case. The precisely planned practice days. Viator learned all of them and so much more from Vicknair.

— — —

Zeb Johnson became a Barbe High School parent while Vicknair was head coach of the Bucs. Johnson’s involvement in the program grew into a role as color analyst for radio broadcasts of Barbe games, booster and coordinator of fundraising events — and, really, whatever the school needed from him for the better part of three decades. Vicknair’s family placed their beloved Charles in Johnson’s hands after his death, making arrangements for services through Johnson Funeral Home.

As investigator for the Calcasieu Parish Coroner’s Office and founder of the funeral home bearing his name, Johnson has been around grieving and memorials longer than he’s been associated with Barbe athletics. The only death he’d seen bring more people through his funeral home and nearby Our Lady Queen of Heaven Catholic Church was that of the latter’s longtime pastor, Msgr. Irving DeBlanc.

“The church was full,” Johnson said, recalling Vicknair’s mid-afternoon funeral the Monday after he died. “I mean, packed, which is about 800 people. We estimated that during the visitation and everything, about 1,000 people came through the funeral home.

“An average funeral, you might have a couple of hundred people that will come by the casket and that would be in the church. A large funeral, just a huge funeral, you’d be looking at 400 people, 450 people. Charles had more than twice what you would expect from a big funeral, a huge funeral.”

The outpouring did not go unnoticed by Vicknair’s family.

“We knew it was a testament to what he’s done for this community,” Cody said.

Johnson understood it two days earlier, when he arrived at the hospital to find a gathering of coaches.

“I happened to be on call that night, then in the morning when the call came in about Charles,” Johnson said. “when I got to the hospital, the parking lot was full of coaches — high school coaches, college coaches. Some of them were in the emergency room.”

It was something Johnson was not accustomed to seeing.

“When somebody calls you and tells you somebody just died, you usually say, ‘Well, I’m sorry to hear that,’ but these guys actually got up and went to the hospital to meet with the family,” he said. “I guess that was also their way of paying tribute to him. You don’t see that. I see a lot of deaths, and to see that many people show up at the hospital, it was something.

“It was like, ‘We’re here because he would be here for us.’ There were people everywhere, there for Charles.”

The more formal gathering for the funeral two days later was unlike anything the South Lake Charles community had ever seen. The entire Westlake football team arrived wearing their black and orange jerseys, the same ones Vicknair volunteered to wash after every game, the ones he cared for with the same attention to detail he brought to all of his duties.

“The players lined up outside the church, and then we moved them inside the church, and they formed an honor guard for us to roll the casket between,” Johnson said.

Ronnie Johns wasn’t able to attend. He and his wife were in Italy, on a two-week trip celebrating their 25th wedding anniversary, and he got a phone call from his brother, Mike Johns, giving him the bad news.

“It literally knocked me to my knees,” Ronnie Johns said. “He was bigger than life, and you say people like that just don’t die that young. It’s way too young to die, and I was just devastated that I could not get back here for that funeral.”

He tried to arrange a flight, but they were 5 or 6 hours from the nearest major airport. It was a weekend, and they couldn’t get a flight booked in time to get them all the way home in time for the funeral.

“That weighed really, really heavy on our hearts that we couldn’t be here, but we made a commitment that we would be there for their family in the coming months and years, and we’ve done that,” Johns said from behind his desk in his Sulphur office. “We spend a lot of time with Debbie, and I talk to his boys all the time, especially the oldest one, Vic, who I tried to be somewhat of a role model for with his career. I talk with him on a weekly basis. We do that.”

Had Johns and his wife been there at the funeral, they would have seen the Westlake Rams in school colors, then a tribute by another team that brought the memorial full circle on many levels and made an impact upon those who followed the funeral procession to the burial site. Barbe players, whose school was on the route from the church to the cemetery, lined up along McNeese Street, dressed in their uniforms for practice and standing at attention as the hearse rolled past them.

“Coach Shaver asked about the procession, and he took all his players who were practicing and walked them out to the neutral ground in front of Barbe,” Johnson said, “and they all stood there as he passed. What the military would do is salute, but the players did the salute by placing their helmets on their hip, bowing their heads as the hearse went by.”

Some of the Barbe players had fathers who were coached by Vicknair.

“They knew this was something important,” Johnson said. “They never met the guy, but they knew that the name Vicknair was synonymous with football at Barbe High School. The kids were really touched by it.”

Johnson said one of the players came to him after the burial and talked with him about Vicknair.

“I never did know him,” Johnson recalled the player saying, “but I had this funny feeling when he passed by. It was something that you can’t describe. It was an emotion that I couldn’t describe, but I knew he was someone very important to the history and the legend of our Barbe football program.”

Johnson connected the dots between the emotion the player struggled to put into words and the father-like connection Vicknair had with so many players and assistant coaches he touched.

“There’s kind of a bond that can’t be explained,” Johnson said. “For three or four months out of the year, these coaches become like a parent. A kid’s got problems in school, and he doesn’t go see his parents — he goes to see his coach. You’ve got issues on and off the field, and the coach is their counselor. That may upset a lot of parents, but that’s a fact. That’s who they come to. They bond with these coaches, and they become parents to the kids.”

Johnson said he’s seen players return to Barbe years after graduation to seek out their former coaches.

“They come back year after year after year and sit down and talk with the coaches,” Johnson said. “They’ll say, ‘I’ve got this problem,’ or ‘I came back to see how you’re doing,’ and Coach Vicknair had that. In fact, he was like a father to those kids and was now in his second or third generation with some families, and he had to give the same advice to the sons that he’d given to their fathers earlier in his career.”

Johnson, who came of age during the Vietnam War and understands how football terms evolved from military language, said there is something about the sport that creates a connection between players and their coaches that features some of the same dynamics found in the various branches of military service.

“They’re out there on Friday nights, playing football,” he said, “and to them, to a lot of them, that’s the closest thing to being in a battle, in a war, that any of them will ever experience. It’s kind of hard to explain, but it’s like a crisis, and the coach is the guy you look to and say, ‘Hey, we’re in a battle here. Help me out.’

“He was that guy. He was the guy that stood up for them and backed them up and took care of them.”

When Westlake played St. Louis later in the 2008 season, the Saints had a special night to honor Vicknair. They wore CV decals on their helmets, displaying the initials of the man who coached his three sons at the school.

Westlake’s players wore the decals too, and both schools kept them on the helmets all season.

Mike Johns, the St. Louis coach, had known Vicknair since they met at McNeese as college students in the early 1960s. Their sons were friends, and they started coaching at the same time.

Johns is one of several Southwest Louisiana Coach of the Year Award winners influenced by Vicknair.

“He’s left a legacy here In Calcasieu Parish,” Anderson said, speaking from the office where he works as assistant superintendent for the school board.

Vicknair’s family continues to learn about that legacy.

“It was kind of a shame that we didn’t know more about him until after the fact,” Vic said.

“But he didn’t want to take credit, never wants to take credit — never did, never will,” Chad said as his older brother nodded, “and I guarantee you he would be mad that we’re talking about him right now. He never wanted to take credit.”

They remembered watching their dad walk around the track at Westlake after a victory, on his way to the equipment room and letting everyone else soak up the celebration and the accolades. It was his way, they said, especially after so many years of being the head coach. It was time to let others be front and center.

Now, the mentor’s former pupils work as head coaches, assistant coaches, businessmen and teachers. To a man, they say it is important for future coaches and players in Southwest Louisiana to know who Charles Vicknair was and the role he played in the development of high school football in the region.

Friends are left with a void to fill.

“I miss him greatly,” Ronnie Johns said a year after Vicknair’s death, “but I was just proud to be a part of his life. I can get pretty emotional about it.”

The family works on one day at a time.

“The emptiness doesn’t go away, but as time goes on you learn how to cope with it,” Cody said. “We’ve done that as a family.”

Talking, it seems, helps.

“We love talking about him and his legacy, because he’d never do it. He’d never talk about his career,” Cody said.

All of our words come back to us in one way or another, it seems, and after the funeral friends and family were left with a reminder of Vicknair’s most remembered expressions. Those sayings would have to do much of the talking for Coach Vic in his absence.

Be careful what you say. We never know how we’re going to be remembered.

Be careful what you say. We never know how we’re going to be remembered.

A slice of heaven? Who would look for heaven in an office of football coaches, on a practice field, from a man who couldn’t spell and couldn’t remember your name? Yes, he often said it in a way that was open to interpretation, but late in the first year after his death, those words had a different ring that resonated with much more poignancy than he ever intended when he spoke them.

As Debbie Vicknair sat quietly on the sofa, nodding in agreement, her youngest son spoke familiar words.

“It’s been a slice of heaven,” Cody Vicknair said. “That is just the story of his life. We were able to see a slice of heaven seeing a coaching legend that was down here for 66 years, and who gave 45 years to just an unsurpassable amount of coaching that he instilled in this community — that brings Southwest Louisiana football to what it is today.”

Tags: Vicknair by admin

3 Comments »

East St. John, coached by Phil Greco and led by quarterback Timmy Byrd, scored in the second and third quarters for a 15-0 lead. Barbe scored on a 7-yard pass from Doug Quienalty to Randy Edwards, and tailback Scott Ayres squeezed over for the two-point conversion that made it a one-possession game with 4:35 left.

East St. John, coached by Phil Greco and led by quarterback Timmy Byrd, scored in the second and third quarters for a 15-0 lead. Barbe scored on a 7-yard pass from Doug Quienalty to Randy Edwards, and tailback Scott Ayres squeezed over for the two-point conversion that made it a one-possession game with 4:35 left. “We played with good players,” Bruchhaus said of their days at Barbe, “and we coached them up. I think when you get to the top, then you coach them up, but you’d better have the players or you’re not going to get to the top.”

“We played with good players,” Bruchhaus said of their days at Barbe, “and we coached them up. I think when you get to the top, then you coach them up, but you’d better have the players or you’re not going to get to the top.” “They’re all grown now, but I remember when they were running around in diapers,” Siebarth said. “We’d be watching film in the film room, and here comes little Vic.”

“They’re all grown now, but I remember when they were running around in diapers,” Siebarth said. “We’d be watching film in the film room, and here comes little Vic.”

Oertling did some research and explained the history of the saying to the players.

Oertling did some research and explained the history of the saying to the players. Bruchhaus said he was strong-willed.

Bruchhaus said he was strong-willed.

Ronnie Johns saw Vicknair as devoted to and worried about his boys as he’d been when they were toddlers. The boys, now adults, were seeing a different aspect of their father.

Ronnie Johns saw Vicknair as devoted to and worried about his boys as he’d been when they were toddlers. The boys, now adults, were seeing a different aspect of their father. “He brought all of his tendencies to deer hunting,” Chad said. “He and I went hunting, and this one time he went in one blind, and I was in another blind, and we get back, and I said ‘I didn’t see much.’ He said, ‘Well, I saw something.’

“He brought all of his tendencies to deer hunting,” Chad said. “He and I went hunting, and this one time he went in one blind, and I was in another blind, and we get back, and I said ‘I didn’t see much.’ He said, ‘Well, I saw something.’ “We never said, “We never get to see him.’ We respected (that their parents) put their energy into their jobs to provide financing for us to get an education, and so we felt honored,” Cody said. “He would come running to us. He really did. We had good times at LSU. We got a condo. He’d spend spring and summer time with us there.”

“We never said, “We never get to see him.’ We respected (that their parents) put their energy into their jobs to provide financing for us to get an education, and so we felt honored,” Cody said. “He would come running to us. He really did. We had good times at LSU. We got a condo. He’d spend spring and summer time with us there.” Max Caldarera asked. Jimmy Shaver asked.

Max Caldarera asked. Jimmy Shaver asked. Be careful what you say. We never know how we’re going to be remembered.

Be careful what you say. We never know how we’re going to be remembered.